|

| The Ninth Street Center |

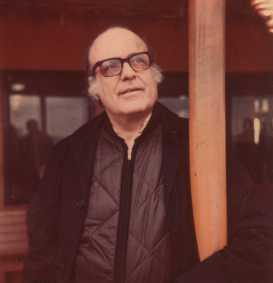

Paul Rosenfels

Paul was a rising star at the University of Chicago in the 1940's, but once he dropped out of the academic system they ignored him for the rest of his life. In 1973 he and I opened the Ninth Street Center, an all-volunteer organization devoted to helping unconventional people live creatively in a sometimes oppressive world. People in need of truth are usually happy to express deep gratitude when they find it, and so this work has been gratifying. Unfortunately for them, the number of university scholars who have sense the importance of his work has remained rather small.

In my nineteen years with Paul I learned that there wasn't anything of importance to human beings that he didn't think about. But he was not a philosopher in the conventional sense; like Bertrand Russell he didn't think much of the problems most philosophers worry about. He cared about ordinary things like human fulfillment and an end to war, and so his primary focus was on human nature and what David Hume had said was the most important task of moral philosophers, the founding of a science of human nature. If you read him thoroughly, you will find some rather amazing passages where he seems to toss-off, almost absent-mindedly, convincing solutions to age old philosophical dilemmas.

Paul used the principle of polarity between femininity and masculinity to describe -- as if for the first time in history -- the dynamics of love and power, honesty and courage, wisdom and strength, depth and vigor, faith and hope, as well as the more abstract categories of time and space, truth and right, tension and energy -- even "causes and effects" and "beginnings and endings." The entire canvas of human nature is described from a single viewpoint within a single semantics. In this sense, he made philosophy a branch of psychology.

We no longer remember the buzzing hive of academics who

argued with Thomas Aquinas about how many angels could dance

on the head of a pin. For similar reasons I believe that

most philosophy being done today will be forgotten in the

centuries to come, and that Paul will come to be considered

the greatest thinker of the 20th century.

For those of us who knew him, though, he was merely a teacher who knew more than anyone else around about human beings. As tremendous as his insights were, he always said he was "only one page ahead of the class." As an imperfect human being himself, Paul was in fact a constant reminder to us of how much we don't know about ourselves.

Paul's descriptions are as clear, as carefully organized and as universally applicable, as if a Martian anthropologist had written us up in the Encyclopedia Galactica. Yet his students are always surprised when all their problems don't immediately vanish in the face of such wisdom. The reason is that science gives us only one kind of knowledge: the kind that can be demonstrated through experience. The kind we often long for, though, is a flash of insight that would constitute the whole story, that would put us into the mind of a god rather than that of earthbound creatures. As finite, transitory, biological organisms whose intellectual hardware evolved to cope with one planetary surface out of trillions, this holistic kind of knowledge is certainly beyond our current grasp. The greatest thinker longs for insights that will spare us tomorrow's tragedy, yet tomorrow's tragedy already comes. Paul felt accutely the tragic nature of the world, and his writings are informed by a compassion for humanity rare in the literature of the social sciences.

Still, science is better than cynism, and -- like the universe itself -- ultimately unbounded. Steven Hawking reminds us that the Grand Unified Theory (whose formula we will be wearing on our teeshirts in 20 years) will not be the end of science but only a new platform upon which bigger questions can be raised. Nor is Paul's work the end of psychology. But from now on, thinkers the world over will see farther into the human landscape because they stand on the shoulders of a giant.

If you'd like to read more about Paul, his autobiography tells his story in great detail. Before you tackle that, though, you should probably read the brief article written about his work in the East Village before the Ninth Street Center was started, as well as the Foreword (and maybe the Introduction I wrote) to his last book. You'll also find samples of his writing style, articles about Paul and his writings, a summary of his basic ideas, and a glossary of the terms that he uses, among the following links.

|

| See a thumbnail sketch of Paul's semantics |

|

| Read about Paul's writing style |

|

| See a Rosenfels glossary |

|

| See a Rosenfels bibliography |

|

| See some quotations about psychological polarity |

|

| See a timeline of polarity awareness |

|

| See a bibliography of psychological polarity |

[D:\dh\web\NSC\3.1\HTP\Paul.htp (127 lines) 2008-01-14 14:31 Dean Hannotte] | ||||||||