Frederick Douglass makes a New Year’s resolution to gain his freedom from slavery (1836)

About this Quotation:

Frederick Douglass took the opportunity of a New Year’s resolution to usher in the year of 1836 to swear that he would attempt to run away from his bondage as a slave. He is deeply aware of his natural right to be free and a burning hatred of his “prison”. What is interesting to note is that his reading matter which inspired these sentiments was a book of speeches used in schools, the Columbian Orator (1st ed. 1797), which provided him with both the theory of individual liberty as well as an historical context in which others had sought their liberty. No wonder that the slave owners made learning to read a crime.

Other quotes from this week:

Other quotes about Colonies, Slavery & Abolition:

- 2009: Emerson on the right of self-ownership of slaves to themselves and to their labor (1863)

- 2009: Sir William Blackstone declares unequivocally that slavery is “repugnant to reason, and the principles of natural law” and that it has no place in English law (1753)

- 2008: Harriet Martineau on the institution of slavery, “restless slaves”, and the Bill of Rights (1838)

- 2007: John Stuart Mill on the “atrocities” committed by Governor Eyre and his troops in putting down the Jamaica rebellion (1866)

- 2007: The ex-slave Frederick Douglass reveals that reading speeches by English politicians produced in him a deep love of liberty and hatred of oppression (1882)

- 2007: Jeremy Bentham relates a number of “abominations” to the French National Convention urging them to emancipate their colonies (1793)

- 2007: Thomas Clarkson on the “glorious” victory of the abolition of the slave trade in England (1808)

- 2007: Jean-Baptiste Say argues that home-consumers bear the brunt of the cost of maintaining overseas colonies and that they also help support the lavish lifestyles of the planter and merchant classes (1817)

- 2007: J.B. Say argues that colonial slave labor is really quite profitable for the slave owners at the expense of the slaves and the home consumers (1817)

- 2006: John Millar argues that as a society becomes wealthier domestic freedom increases, even to the point where slavery is thought to be pernicious and economically inefficient (1771)

- 2006: Adam Smith notes that colonial governments might exercise relative freedom in the metropolis but impose tyranny in the distant provinces (1776)

- 2005: Less well known is Thomas Jefferson’s First Draft of the Declaration of Independence in which he denounced the slave trade as an “execrable Commerce” and slavery itself as a “cruel war against nature itself” (1776)

28 December, 2009

| Frederick Douglass makes a New Year’s resolution to gain his freedom from slavery (1836) |

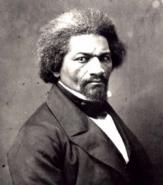

Frederick Douglass (1817-1895) must have been 19 or so when he made a solemn vow as part of his New Year’s resolutions for 1836 to exercise his “natural and inborn right” to be free by escaping the “hell of horrors” which was slavery:

I AM now at the beginning of the year—1836—when the mind naturally occupies itself with the mysteries of life in all its phases—the ideal, the real, and the actual. Sober people look both ways at the beginning of a new year, surveying the errors of the past, and providing against the possible errors of the future. I, too, was thus exercised. I had little pleasure in retrospect, and the future prospect was not brilliant. “Notwithstanding,” thought I, “the many resolutions and prayers I have made in behalf of freedom, I am, this first day of the year 1836, still a slave, still wandering in the depths of a miserable bondage. My faculties and powers of body and soul are not my own, but are the property of a fellow-mortal in no sense superior to me, except that he has the physical power to compel me to be owned and controlled by him. By the combined physical force of the community I am his slave—a slave for life.” With thoughts like these I was chafed and perplexed, and they rendered me gloomy and disconsolate. The anguish of my mind cannot be written.

The full passage from which this quotation was taken can be be viewed below (front page quote in bold):

Chapter XIX. The Runaway Plot

I AM now at the beginning of the year—1836—when the mind naturally occupies itself with the mysteries of life in all its phases—the ideal, the real, and the actual. Sober people look both ways at the beginning of a new year, surveying the errors of the past, and providing against the possible errors of the future. I, too, was thus exercised. I had little pleasure in retrospect, and the future prospect was not brilliant. “Notwithstanding,” thought I, “the many resolutions and prayers I have made in behalf of freedom, I am, this first day of the year 1836, still a slave, still wandering in the depths of a miserable bondage. My faculties and powers of body and soul are not my own, but are the property of a fellow-mortal in no sense superior to me, except that he has the physical power to compel me to be owned and controlled by him. By the combined physical force of the community I am his slave—a slave for life.” With thoughts like these I was chafed and perplexed, and they rendered me gloomy and disconsolate. The anguish of my mind cannot be written.

At the close of the year, Mr. Freeland renewed the purchase of my services from Mr. Auld for the coming year. His promptness in doing so would have been flattering to my vanity had I been ambitious to win the reputation of being a valuable slave. Even as it was, I felt a slight degree of complacency at the circumstance. It showed him to be as well pleased with me as a slave as I with him as a master. But the kindness of the slave-master only gilded the chain, it detracted nothing from its weight or strength. The thought that men are made for other and better uses than slavery throve best under the gentle treatment of a kind master. Its grim visage could assume no smiles able to fascinate the partially enlightened slave into a forgetfulness of his bondage, or of the desirableness of liberty.

I was not through the first month of my second year with the kind and gentlemanly Mr. Freeland, before I was earnestly considering and devising plans for gaining that freedom, which, when I was but a mere child, I had ascertained to be the natural and inborn right of every member of the human family. The desire for this freedom had been benumbed while I was under the brutalizing dominion of Covey, and it had been postponed and rendered inoperative by my truely pleasant Sunday-school engagements with my friends during the year at Mr. Freeland’s. It had, however, never entirely subsided. I hated slavery always, and my desire for freedom needed only a favourable breeze to fan it into a blaze at at any moment. The thought of being only a creature of the present and the past troubled me, and I longed to have a future—a future with hope in it. To be shut up entirely to the past and present is to the soul whose life and happiness is unceasing progress—what the prison is to the body—a blight and mildew, a hell of horrors. The dawning of this, another year, awakened me from my temporary slumber, and roused into life my latent but long-cherished aspirations for freedom. I became not only ashamed to be contented in slavery, but ashamed to seem to be contented, and in my present favourable condition under the mild rule of Mr. Freeland, I am not sure that some kind reader will not condemn me for being over ambitious, and greatly wanting in humility, when I say the truth, that I now drove from me all thoughts of making the best of my lot, and welcomed only such thoughts as led me away from the house of bondage. The intensity of my desire to be free, quickened by my present favourable circumstances, brought me to the determination to act as well as to think and speak. Accordingly, at the beginning of this year 1836, I took upon me a solemn vow, that the year which had just now dawned upon me should not close without witnessing an earnest attempt, on my part, to gain my liberty, This vow only bound me to make good my own individual escape, but my friendship for my brother-slaves was so affectionate and confiding that I felt it my duty, as well as my pleasure, to give them an opportunity to share in my determination. Toward Harry and John Harris I felt a friendship as strong as one man can feel for another, for I could have died with and for them. To them, therefore, with suitable caution, I began to disclose my sentiments and plans, sounding them the while on the subject of running away, provided a good chance should offer. I need not say that I did my very best to imbue the minds of my dear friends with my own views and feelings. Thoroughly awakened now, and with a definite vow upon me, all my little reading which had any bearing on the subject of human rights was rendered available in my communications with my friends. That gem of a book, the Columbian Orator, with its eloquent orations and spicy dialogues denouncing oppression and slavery—telling what had been dared, done, and suffered by men, to obtain the inestimable boon of liberty, was still fresh in my memory, and whirled into the ranks of my speech with the aptitude of well-trained soldiers going through the drill. I here began my public speaking. I canvassed with Henry and John the subject of slavery, and dashed against it the condemning brand of God’s eternal justice. My fellow-servants were neither indifferent, dull, nor inapt. Our feelings were more alike than our opinions. All, however, were ready to act when a feasible plan should be proposed. “Show us how the thing is to be done,” said they, “and all else is clear.”

We were all, except Sandy, quite clear from slave-holding priestcraft. It was in vain that we had been taught from the pulpit at St. Michaels the duty of obedience to our masters; to recognise God as the author of our enslavement; to regard running away as an offence, alike against God and man; to deem our enslavement a merciful and beneficial arrangement; to esteem our condition in this country a paradise to that from which we had been snatched in Africa; to consider our hard hands and dark colour as God’s displeasure, and as pointing us out as the proper subjects of slavery; that the relation of master and slave was one of reciprocal benefits; that our work was not more servicable to our masters than our masters’ thinking was to us. I say it was in vain that the pulpit of St. Michaels had constantly inculcated these plausible doctrines. Nature laughed them to scorn. For my part, I had become altogether too big for my chains. Father Lawson’s solemn words of what I ought to be, and what I might be in the providence of God, had not fallen dead on my soul. I was fast verging toward manhood, and the prophecies of my childhood were still unfulfilled. The thought that year after year had passed away, and my best resolutions to run away had failed and faded, that I was still a slave, with chances for gaining my freedom diminished and still diminishing—was not a matter to be slept over easily. But here came a trouble. Such thoughts and purposes as I now cherished could not agitate the mind long, without making themselves manifest to scrutinizing and unfriendly observers. I had reason to fear that my sable face might prove altogether too transparent for the safe concealment of my hazardous enterprise. Plans of great moment have leaked through stone walls, and revealed their projectors. But here was no stone wall to hide my purpose. I would have given my poor tell-tale face for the immovable countenance of an Indian, for it was far from proof against the daily searching glances of those whom I met.